How sports became a refuge for county teenager from Wheatmore

Johnathan Kelly receives treatment at halftime during Wheatmore’s football game last September at East Davidson. (Bob Sutton / Randolph Record)

Without his natural parents, a multi-sport athlete from Wheatmore went through many life changes prior to and during high school

TRINITY — When Johnathan Kelly tried to plow his way through the line of scrimmage for Wheatmore’s often-overwhelmed football team and was pushed back, the thing he wanted most was another chance.

When he came off the wrestling mat following a match cut short by a bigger opponent, he looked forward to another bout with a better outcome.

He had learned to overcome obstacles and trauma in a childhood that could have led down a less-inviting path.

Instead, he did more than endure, he often excelled.

Kelly, as a member of the Class of 2025, completed a high school athletic career that at one time included four varsity sports. It was such a combination that as a junior he competed in basketball and wrestling during the same season – who does that?

But football was always the activity that provided the greatest satisfaction and a much-needed outlet.

His time as a determined athlete in Wheatmore’s athletics department came following a challenging childhood. Boths parents died from what were described as overdoses.

His father died in 2015, then his mother dying in May 2020.

Kelly found the right family with Chris and Holly Strickland and their three children, including twin sons in the same grade as Kelly.

He also had the desire to play football.

“When you talk perseverance, he’s that kid,” said Wheatmore football coach Jacob Sheffield, who was in his first season in 2024. “The things he has experienced in his very young life.”

After contemplating going to a Division III school to play football, he has opted for another route. He has committed to four years in the Marines, expecting to report later this summer.

That will be the next chapter in a life that has been stocked with countless life experiences.

Kelly, 18, finished at Wheatmore touting a grade point average above 3.0 – and a hefty list of admirers.

“It’s amazing he has turned out as well as he has,” said Rick Halo, an assistant football coach and former athletics director. “He’s one of the best kids we have at the school. He could have a grudge.”

Kelly moved beyond that.

“Football helps,” he said. “You don’t think about anything else. You just play.”

Because of football, he created his own type of offensive line to block out negative influences. In earlier more chaotic years, he was faced with decisions.

“I would see how they were acting,” he said of those around him. “They would offer me the blunts. I would say ‘no.’ I wanted to play football.”

He was outside riding a bicycle when the incident occurred that led to his mother’s death.

“It wasn’t the first time my mom had an overdose,” he said. “I knew. I wasn’t dumb. She probably didn’t know I knew, but it was obvious.”

Then it was clear that there would be more changes for Kelly, who was a middle schooler at Uwharrie Ridge Six-Twelve. He might have been pegged to advance to Southwestern Randolph before another route developed.

Learning curves

The Stricklands were available to help. He had spent chunks of time at their home, so there was a familiarity.

“I was staying with them,” he said. “After a few weeks, my (older) sister was good with that.”

As the process unfolded, they became his legal guardians.

“It wasn’t a hard decision to make at all,” Holly Strickland said. “We already had three (children) so we learned to make it work. … He was always with us, so when his mother passed …”

During that ensuing process, there was a session in court as legal custody was approved.

“In front of a judge, it was kind of weird,” Kelly said.

Holly Strickland recognized the awkwardness of court for a child.

“He had to watch us talk about all that,” she said.

Holly is an apartment manager in Greensboro. Chris has a construction company.

The Stricklands appreciate that they had the opportunity for a heightened role. They know what Kelly faced before that wasn’t easy.

“Looking back, if he had taken that one wrong turn at that age, it could have been a bad road,” Chris Strickland said.

Yet it wasn’t always an easy transition. He wasn’t used to living with them full-time and it took time before his behavior fell in line.

“It was something we never expected and kind of took things as it comes,” Chris Strickland said of adding to the family.

“He came from a house he could do what he wanted,” Holly said. “We learned each other’s ways. He has definitely taught us things and we’ve taught him things. It has been a journey.”

A few years later, the networking of teenagers connected to the Stricklands had bloomed tremendously, much because of Kelly’s rising list of friends.

“He’s a blender because he blends with everybody,” Chris Strickland said.

One of those friends was classmate Drew Hammonds, who recalled meeting Kelly in middle school. They were in the eighth grade when his new friend visited his home for the first time.

“We were talking and he told me about his life story,” Hammonds said. “I thought, ‘How is he this strong to handle all this?’ ”

Fixation on football

Football became an outlet since he was signed up to play on the pee wee level.

“That first year, I did not like to get hit,” Kelly said. “The second year, I was practicing all the time.”

That’s also how he became acquainted with the Stricklands, though they weren’t always on the same side. Chris Strickland was a youth coach and it became clear to him that Kelly was going to be a menace on the field.

“He was a big kid,” Holly Strickland said. “Before I ever knew him, he gave (our son) Gavin his first-ever concussion.”

When he joined his new family, he became even bigger, but not how he preferred.

“That eighth grade year I was distracted, got chubby,” he said, noting his weight grew to 210 pounds. “My body wasn’t used to eating that much, and I eat a lot. I got big.”

But in high school his conditioning improved and it became evident he could help the Warriors.

“I always say the football field was his happy place,” Holly Strickland said.

Kelly was so essential to Wheatmore’s football program that he was making major impacts as a freshman.

That continued all the way to the final games of his career last fall. He ran 99 yards for a touchdown against Providence Grove on a night he hadn’t been feeling well. He arrived back on the sideline, and puked.

“All right, you’re back on defense,” Sheffield said in response.

Wheatmore was the constant underdog, but Kelly said he couldn’t be consumed with that.

“I just got to play. I got to try to perform. Can’t let it bring you down,” he said. “I didn’t think about the score when I play. I just keep playing.”

Dominic Hittepole, who became a state champion wrestler for Wheatmore, is a year younger than Kelly. He happened to play the same positions on the football field.

“My freshman year in football, he mentored me,” said Hittepole, who realized all the way through the 2024 season why he had limited playing time. “He never subs out. I was behind him, but didn’t get in.”

Upon taking the job, Sheffield quickly discovered Kelly had special traits.

“He makes me laugh and even chuckle a little bit,” the coach said. “You get one every so often at the school you’re at. He’s that kid you want to pull for.”

Two for one

The winter sports season of 2023-24 was without rest for Kelly.

Coming off football season and before track and field season, he had plenty going on. He had been in the basketball program, but the wrestling team needed someone in the upper weights.

“He did it. He would literally come to wrestling practice after school every day and from there go straight to basketball practice,” wrestling coach Kyle Spencer said. “If he had a game or something, he would practice for a little while with us and go get ready for his game. We just kind of worked around it. It worked out good in our favor.”

By his senior season, he put basketball on pause. He opted for wrestling as a winter sport.

“You can’t train the heart, you can’t train the hard work, what he has put in,” Spencer said. “That’s why he has gotten so much better since last year.”

At the wrestling team’s Senior Night, there was a trio of dual meets. Kelly weighed in at 193 pounds to compete in the 215 class.

“People came to watch me,” he said, appreciating the support.

After a loss against Greensboro Page, it took Kelly less than a minute to flatten a Bishop McGuinness opponent, albeit with an unorthodox maneuver.

Then came an encounter with Greensboro Grimsley strongman Andrew Hassard, an eventual state qualifier in Class 4A. A few youngsters gathered in front of the bleachers to offer encouragement.

Their message: “You got this JK! You got this JK!”

Kelly rode him hard from the top in the third period, but couldn’t get a turn and lost by decision.

He walked off the mat, tossed down his headgear and exited to the lobby. A few minutes later, back in the team bench area, he had his arms around Hammonds and Hittepole.

“I need that. It still sucks,” he said. “Ain’t nothing wrong with it. I needed the conditioning.”

Yet moments like that added to his internal fire and to his collective experiences on the mats.

Hittepole and Kelly were frequent practice partners.

“I try to get him prepared,” Hittepole said. “Sometimes it’s not fun for him. Sometimes it’s not fun for me.”

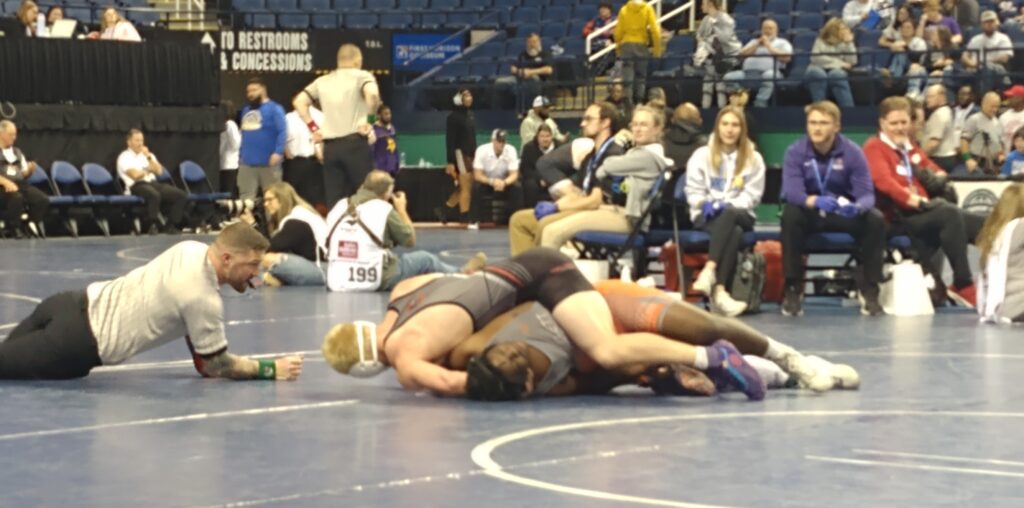

A few weeks later in the Class 2A Mideast Regional in Lexington, Kelly was a significant underdog. Only the top four finishers advance to the state tournament. He was seeded eighth.

By the time he knocked off the top seed and then avenged a loss from earlier in the season in the semifinals, he had clinched a state-tournament berth.

“I was hyped,” he said. “Honestly, I didn’t think I was going to make states this year. I was worried. I came in here and I just wrestled.

“I bet a bunch of people didn’t think I was going to make it. Because I was the 8 seed and I had almost 20 losses. They probably just look at that and say, ‘Oh, he’s not good.’ But record don’t mean anything.”

Kelly lost in the regional final, but his season was extended. He said it’s paramount to never lose sight of the goals.

“Last year, I couldn’t make a six-minute match. I’d be dead after the first or second period. This year, I’ve had a bunch of ride-outs where I’d ride him out to win. Six minutes. … Coaches and teammates, really. They push you through practice and make you get better. It’s really all them, honestly. They help you with a lot, so much.”

There was barely time for reflection on this Saturday in mid-February. In a sport that had been an afterthought until the past couple of years, he was suddenly going to compete in the state tournament.

“No giving up. Got that grit,” he said outside the gym.

Where do you think that came from?

“My mom. She wouldn’t quit whatever she was doing,” he said. “I’d stay I got it from her. … Got to show them what she gave me.”

Hittepole said Kelly’s rise in wrestling seemed out of ordinary.

“I got him to wrestle last year,” he said. “This year, he’s a state qualifier. He won when it really mattered.”

Kelly split two matches on the first day of the state tournament. The next day, he trailed an elimination bout vs. Joseph Spencer of Manteo by 6-0 going to the third period. It was 10-10 late in the match before his career on the mats ended in a 13-10 defeat.

That came almost nine hours after he arrived at the coliseum.

“So close. I don’t know how I didn’t finish,” he said.

Lasting impact

After the basketball/wrestling combination, it wasn’t surprising that Kelly’s track and field pursuits came as a thrower of the discus and shot put and as a sprinter – another unconventional combination.

He left an impression along the way at Wheatmore.

“When you talk about John Kelly, you talk about someone who has every reason in the world to be mad at it,” Coach Spencer said. “You have no reason to respect elders, no reason to really feel like he owes anybody anything. That’s a complete opposite of what he represents. He is all about helping people, serving people, doing what he’s asked and then going above and beyond that anytime the opportunity presents itself.

“Everybody loves JK. Everybody loves him. That’s because of his personality.”

Spencer said there was much more than the athletics.

“He’s a peer tutor in one of our special needs classes,” he said. “That’s pretty awesome. He could have taken that period off and just not had class and took some other elective that was easier. But he chose to do that to be in that class with those kids.”

So Kelly’s impact also spread to those who know him well.

“It made me to appreciate things in life,” Hammonds said knowing what his friend had been through.

Kelly was selected by school staff as a Senior of Valor, a special distinction at the school. The first attempt at the group photo had to be taken a second time.

“I was the only one mean mugging ‘em,” he said. “So they were telling me to smile, so I smiled. Just mugshot. That’s how I am, just be normal. Just straight-facing it.”

Kelly said personal losses as a young child and those in sports competitions have all made a difference in his life.

“I can’t complain if I’m losing because I’m getting better,” he said. “The world is not going to stop. It’s going to keep happening.”

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram