Strong opinions expressed over proposed Randolph County ‘harm reduction’ plan

ASHEBORO — Strong opinions were expressed during a faith-heavy discussion about a proposed “harm reduction” plan during a May 22 meeting of the Randolph County Opioid-Drug Community Collaborative.

The Collaborative was established through funding by the county board of commissioners in 2016. Per Jennifer Layton, assistant health director for Randolph County’s public health department, the Collaborative convened in 2017 with community partners to launch its coalition, and in the timespan between 2017 and 2019, the Collaborative began implementing its initial action plan.

The afternoon meeting was held at the AVS Catering and Banquet Center in Asheboro. The public information officer for Randolph County said the meeting had been posted on county social media platforms on May 18, and Layton said there was no public notice posted because it was a “coalition meeting.” Despite the short timeframe, an estimated crowd of nearly 150 showed up.

The main presentation on harm reduction was given by Jennifer Layton.

Remarks were also given by a panel consisting of Elizabeth Brewington, Manager of Health Programs for the N.C. Association of County Commissioners; Pastor Allen Murray of the Asheboro-area “Faith in Motion Ministries;” and Robi Cagle, the program coordinator for the Uwharrie Harm Reduction Initiative.

A tense and, at times, emotional question and answer session followed the presentations and remarks by the panel.

Several faith leaders from Randolph County and the Asheboro area expressed strong opposition to part of the harm reduction plan that involved a program that would supply clean needles to addicts, referred to as a syringe services program or SSP.

The General Assembly authorized SSP’s in 2016 to create needle and hypodermic syringe exchange programs. The intent of the law was an effort to promote “scientifically proven ways of mitigating health risks associated with drug use and other high-risk behaviors.”

Dr. Jonathan Burris, a pastor for the New Center Christian Church, located in Seagrove, cited the low rates of needles returned or collected associated with SSP’s. Burris said he was also a data scientist with his own consulting firm that works in the area of statistics, data analysis, artificial intelligence, and heuristics.

“I like numbers. Numbers do not lie,” said Burris. He went on to cite the North Carolina Safer Syringe annual report from 2021 and 2022, which he said shows that “there are more needles and more naloxone being served to the same people year over year.”

Naloxone is a medication similar to Narcan, which rapidly reverses an opioid overdose.

“How is this not facilitating more drug addiction when only 5% are actually referred to treatment?” Burris asked. “In addition to that, we see that 19.4 million needles have been distributed. Only 6.9 million have been recovered. That means that 65% of that 19.4 million – over 12 million needles – are unaccounted for.”

Burris pressed the point, saying that he had heard Harm Reduction was collecting the needles, but wondered who had collected the needles from a “bucket” in front of a “local Asheboro business down the street” in the last year.

“It was not the folks doing the Harm Reduction,” said Burris. “It was the business owner.”

“I appreciate the sentiments here, but this is not the solution,” said Todd Nance, a pastor from Ramseur. “These people need help, but I don’t think clean needles is the solution.”

Other attendees, including the pastors present, spoke of finding used needles on the playground areas of their churches as well as drug deals going down at night in their church parking lots.

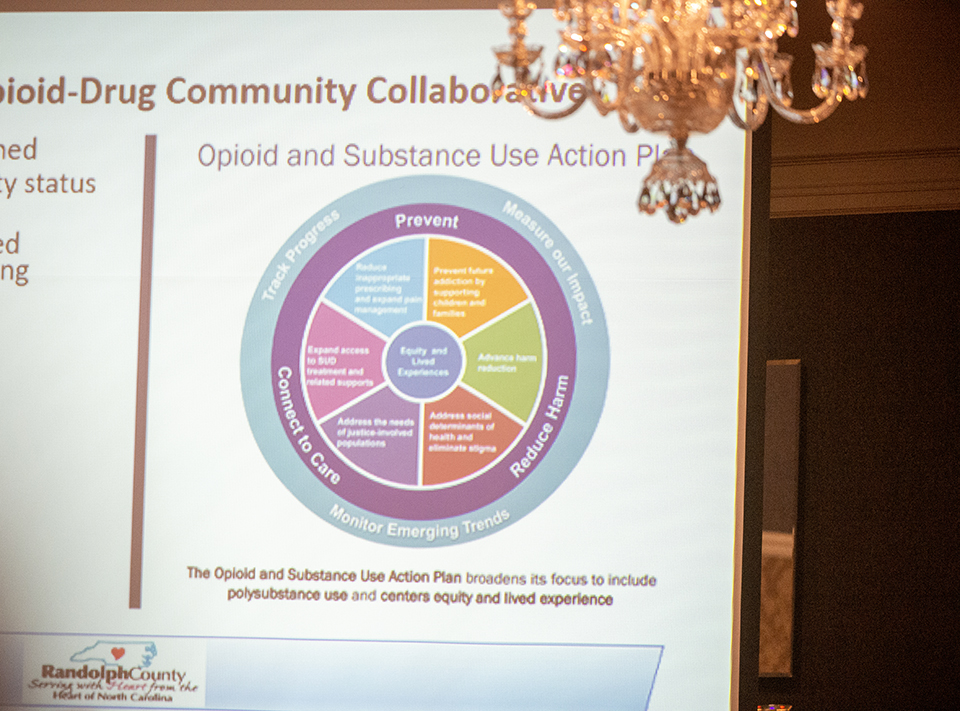

Layton referred to the N.C. Department of Health and Human Services’ “Opioid and Substance Use Action Plan” as a basis for the work of the Collaborative. The state’s plan includes three components: prevention, reducing harm, and connecting with care.

One slide described the “core values” of Harm Reduction as overlapping the concepts of “love, compassion, and kindness,” while another billed Harm Reduction as “a social justice movement” to “respect the rights of people who use drugs,” and a “practical set of strategies” to reduce negative impacts of drug abuse.

Another slide cited 2021 statistics that 11 North Carolinians die each day of a drug overdose, and eight of those deaths were opioid-related. An additional statistic on the same slide cited 32,000 North Carolinians had died of a drug overdose between 2000 and 2021.

According to the Randolph County Opioid Resources data dashboard, there have been 257 drug overdoses resulting in 28 fatalities so far in 2023. The heat map associated with the 2023 data shows a concentration in Asheboro and in the High Point/Archdale area.

The data for past years show a steady increase in both overdoses in the county, with 786 overdoses and 84 fatalities in 2022, 610 overdoses and 82 fatalities in 2021, 576 overdoses and 53 fatalities in 2020, and 664 overdoses resulting in 36 deaths in 2019.

The data dashboard does not indicate if the data is all opioid-related overdoses or if it includes other drugs.

Layton warned about making “dangerous assumptions” about the plan and directed those in attendance to “come ask questions from those doing the work.”

Part of Layton’s presentation included a short video of Reverend Michelle Mathis, the executive director of “Olive Branch Ministries,” a “faith-based harm reduction” organization that serves Allegheny, Ashe, Burke, Catawba, Cleveland, Gaston, Lincoln, McDowell, and Watauga Counties. In the video, Mathis compares the story of Lazarus in the Bible to that of helping addicts recover, stating near the closing that “this work is messy but also miraculous.”

Rep. Neal Jackson (R-Randolph) was on hand to give an invocation at the start of the meeting, as were several of the county’s commissioners, including Chairman Darrell Frye and Kenny Kidd.

Frye opened the meeting with some brief comments which referenced the county commissioner’s intent to deal with the opioid crisis per its 2016 Strategic Plan and the $9,825,790 million in settlement money apportioned to Randolph County for funding the county’s opioid response.

In June 2022, N.C. Attorney General Josh Stein announced local governments would begin receiving the first payments from a $26 billion national opioid agreement with the nation’s three major drug distributors (Cardinal, McKesson, and AmerisourceBergen) and Johnson & Johnson. The release stated that the fund distribution could be accessed through the Community Opioid Resources Engine for North Carolina (CORE-NC).

Per the NC-CORE dashboard, so far, Randolph County has received $1,209,154 in two payments during 2022; $377,436 in the spring and $831,718 in the summer.

According to Frye, the over $9.8 million breaks down to $1 million in funding a year that will stretch for the next 18 years as a result of two settlements, one with Purdue Pharma and another dealing settlement money obtained from a lawsuit against distributors of opioids like CVS and Walgreens pharmacies.

“I don’t think the needle distribution program is a good idea, and I agree that if there’s a 150 people here, 100 of them came to say this needle thing is a crazy idea.”

Commissioner Kenny Kidd

Frye mentioned the settlement funds the county has received come with “directed issues and procedures to be followed.” According to the opioid settlement website, a Memorandum of Agreement offers local governments two options for spending the money. Option A is a list of 12 approved strategies to choose from. Option B is a “collaborative strategic planning process” that includes an expanded approved list of strategies.

“We can’t save a soul or rehabilitate a person who is dead,” Frye told the audience. He went on to say that “County Commissioners have not [yet] made decisions or directed any money. This is part of the conversation today.”

In an interview with North State Journal, Kidd said that while the Collaborative was convened to offer solutions, the commissioners would be the deciding factor in what strategies would ultimately be employed.

“The commissioners will decide what to do and what not to do,” said Kidd. “Ultimately, we will make the decision – the five of us.” He indicated the topic might be brought up at the next meeting of the board of commissioners in June.

“A month ago, they [the Collaborative] came to us with proposals for the $1.2 million dollars, and there are about eight different strategies they are going to address with the rollout of those $1.2 million dollars,” said Kidd. “The commissioners tabled it because we knew this meeting was coming up, and it would be a good time for public discussion.”

When asked about the majority of the meeting’s attendees opposing a needle program, Kidd said he “agreed with that assessment.”

Kidd also provided North State Journal with images of syringes found around the Asheboro area.

“It’s Randolph County… it’s a pretty conservative community,” said Kidd, noting the area is a strong, faith-based community. “I don’t think the needle distribution program is a good idea, and I agree that if there’s 150 people here, 100 of them came to say this needle thing is a crazy idea.”

“It is not condoning. It is not enabling,” Murray said during his panel remarks about providing support services, such as clean needles to addicts. “It’s giving them one more chance.” He later added, “They’re [addicts] going to use anyway.”

Murray’s Faith In Motion Ministries is relatively new and was formed as a non-profit in August 2021. Murray told North State Journal his organization is non-denominational.

During his comments, Murray also alluded to the fact he is a recovering addict and told the audience not to let politics become more important than people.

The panel did not include a representative of the “Community Hope Alliance,” which handouts for the meeting indicate is leading the harm reduction workgroup. The contact for Community Hope Alliance is Kelly Link, who may have been in attendance but was not on the panel.

Among the other materials given out was a “Stop the Stigma” flier offering alternative language to terms such as drug abuse, addicts, and junkies, as well as terms like clean and dirty needles. Instead, the flier suggested terms like “substance abuse disorder,” “person with substance abuse disorder,” and “sterile/used syringes.”

The next meeting of the Randolph County Opioid-Drug Community Collaborative is scheduled for July 24.

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram